Source(Google.com.pk)

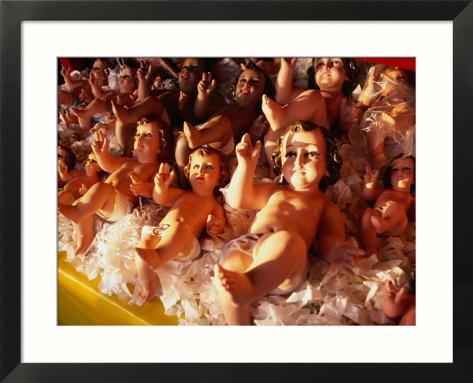

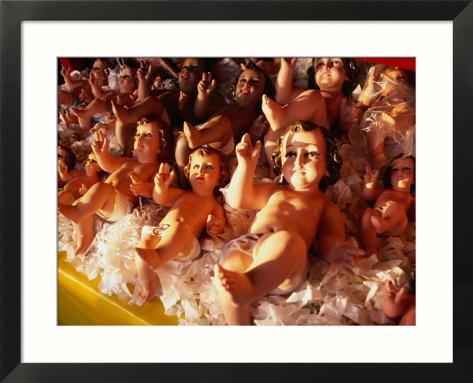

Baby Jesus Dolls Biography

"The woman who had the image in the chest, when they came into fine cities, took the image out of her chest and set it in the laps of respectable wives. And they would dress it up in shirts and kiss it as though it had been God himself."

Children

Entertainment:

Dolls were toys known as mawmets or poppets, and the earliest references were to rag dolls that were made by little girls themselves. Like other medieval toys, dolls could have been given by adults for an adult purpose, but they may have also been used by children in original ways; that is, they are referenced as babies for children, suggesting that little girls pretended to be a mommy, similarly to the baby doll of today. This evidence suggests that for children, and more specifically girls, dolls were used for playtime and make-believe.1

Imitation:

It is believed that much like childhood today, much of the medieval children’s culture is based off of imitation of adult culture, which is the case with dolls. Just as the women in The Book of Margery Kempe dressed and played with the baby Jesus devotional doll described by Margery Kempe, children also cared for their dolls and played pretend. While playing with toys may seem to be the activity most specific to children, and the most distinct from the culture of adults, ultimately a child’s toy a reflection of adults’ model—making and –collecting.2

Adults

Occupational:

For some craftsmen, making dolls served as a means to make a living. By 1300, craftsmen were producing model toys which imitated objects from adult life. Many of those recovered in England are metal ones made of lead-tin alloy using molds, and were therefore capable of being mass-produced. Dolls crafted from professionals were most likely made of wood or other sturdy material to withstand transport and sold in shops, at fairs or by peddlers, and generally sold to children of wealthier families. Poor children could usually make toys by themselves from scrap materials found at hand, but they may have also been given goodquality toys thanks to skillful fathers.3

Religious:

In medieval times, dolls were adult objects as well.4 In her autobiography, Margery Kempe recounts watching women on her pilgrimage express their reverence to Christ by dressing and playing with the image of the baby Jesus devotional doll; Kempe is so overwhelmed with happiness at their open appreciation of the Lord Jesus that she begins to shudder from sobbing in gratitude. Their actions show a high form of worship and she is so pleased that she weeps with joy.5 There are reports of similar dolls of Christ and Mary that were carried around by women in northern England during the Advent,6 which is the ecclesiastical calendar referring to the season immediately preceding the festival of the Nativity (now including the four preceding Sundays),7 suggesting that adult dolls were typically religious items.

The Book of Margery Kempe

In her autobiography, Kempe describes her experience as a wife, mother and woman seeking a higher form of devotion to the Lord in the 1400s. While Kempe is on pilgrimage to Venice, she writes of two approaching Grey Friars and a woman that came with them from Jerusalem, and she had with her an ass, which was bearing a chest containing an image of our Lord. Kempe’s story shows an example of the a doll as a devotional artifact, initially leaving it ambiguous, but then delving deeper into its’ description:

The woman who had the image in the chest, when they came into fine cities, took the image out of her chest and set it in the laps of respectable wives. And they would dress it up in shirts and kiss it as though it had been God himself. And when the creature [Kempe] saw the worship and the reverence that they accorded the image, she was seized with sweet devotion and sweet meditations, so that she wept with great sobbing and loud crying. And she was so much more moved because, while she was in England, she had high meditations on the birth and the childhood of Christ and she thanked God because she saw each of these creatures have as great faith in what she saw with her bodily eye as she had before with her inward eye.

In the description, the existence of the “ass” and the act of dressing the image in shirts lead the reader to see Christ’s image in that of the baby Jesus. Finally, Kempe explicitly expresses that when she exclaims her “high meditations on the birth and the childhood of Christ.” The extreme emotions reflected here with the sobbing, and shuddered and complete sense of feeling overwhelmed with love towards a non-living baby starkly contrasts with the other extreme lack of emotions with her own children.8

Alternatively, at the beginning of the book Kempe repetitively depicts instances where she wishes

to be chaste, but must allow her husband to have his way with her, and then she would say in as much as a few words or at most a line expressing that she then had a child. For instance, after begging to be chaste, her husband responds saying, “it was good to do so, but he might not yet – he would do so when God willed. And so he used her as he had done before, he would not desist. And all the time she prayed to God that she might live chaste,” but since she could not deny her husband her body because of the marriage debt law, she expressed her grief by inflicting, “great bodily penance […] and bore him children during that time." The language here seems so detached, especially in reference to her children, to her own flesh and blood. Not only is there little information about the “children” referenced above, such as their genders, age or name, but the language itself is so detached, use of “bore” makes it seem like her wifely duty to her husband to carry children, but she doesn’t feel any internal motherly connection to them. “Bore” could also be seen as a pun, further expressing Kempe’s disinterest in child rearing, as representing motherhood as a bore.

Analyists rationalize Kempe’s behavior by “[presuming] that the physical absence of Margery's children in her account, except for isolated allusions, represents an abandonment and rejection of her own maternalism in favour of pursuing the spiritual life”. Considering this argument, Kempe’s other devout actions reiterate the presumption because throughout the novel, Kempe continually attempts to shun the Earthly material and focus on only the Holy, and that this would also include the rejection of her Earthly children. To be a mother to a limited amount of children in a limited sphere would forever prevent her from a personal experience of the body of Christ in all aspects of life, so instead Kempe finds empowerment through imitatio Mariae, merging with the persona of the Virgin whilst on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, to become mother to the whole world.10 Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls Biography

"The woman who had the image in the chest, when they came into fine cities, took the image out of her chest and set it in the laps of respectable wives. And they would dress it up in shirts and kiss it as though it had been God himself."

Children

Entertainment:

Dolls were toys known as mawmets or poppets, and the earliest references were to rag dolls that were made by little girls themselves. Like other medieval toys, dolls could have been given by adults for an adult purpose, but they may have also been used by children in original ways; that is, they are referenced as babies for children, suggesting that little girls pretended to be a mommy, similarly to the baby doll of today. This evidence suggests that for children, and more specifically girls, dolls were used for playtime and make-believe.1

Imitation:

It is believed that much like childhood today, much of the medieval children’s culture is based off of imitation of adult culture, which is the case with dolls. Just as the women in The Book of Margery Kempe dressed and played with the baby Jesus devotional doll described by Margery Kempe, children also cared for their dolls and played pretend. While playing with toys may seem to be the activity most specific to children, and the most distinct from the culture of adults, ultimately a child’s toy a reflection of adults’ model—making and –collecting.2

Adults

Occupational:

For some craftsmen, making dolls served as a means to make a living. By 1300, craftsmen were producing model toys which imitated objects from adult life. Many of those recovered in England are metal ones made of lead-tin alloy using molds, and were therefore capable of being mass-produced. Dolls crafted from professionals were most likely made of wood or other sturdy material to withstand transport and sold in shops, at fairs or by peddlers, and generally sold to children of wealthier families. Poor children could usually make toys by themselves from scrap materials found at hand, but they may have also been given goodquality toys thanks to skillful fathers.3

Religious:

In medieval times, dolls were adult objects as well.4 In her autobiography, Margery Kempe recounts watching women on her pilgrimage express their reverence to Christ by dressing and playing with the image of the baby Jesus devotional doll; Kempe is so overwhelmed with happiness at their open appreciation of the Lord Jesus that she begins to shudder from sobbing in gratitude. Their actions show a high form of worship and she is so pleased that she weeps with joy.5 There are reports of similar dolls of Christ and Mary that were carried around by women in northern England during the Advent,6 which is the ecclesiastical calendar referring to the season immediately preceding the festival of the Nativity (now including the four preceding Sundays),7 suggesting that adult dolls were typically religious items.

The Book of Margery Kempe

In her autobiography, Kempe describes her experience as a wife, mother and woman seeking a higher form of devotion to the Lord in the 1400s. While Kempe is on pilgrimage to Venice, she writes of two approaching Grey Friars and a woman that came with them from Jerusalem, and she had with her an ass, which was bearing a chest containing an image of our Lord. Kempe’s story shows an example of the a doll as a devotional artifact, initially leaving it ambiguous, but then delving deeper into its’ description:

The woman who had the image in the chest, when they came into fine cities, took the image out of her chest and set it in the laps of respectable wives. And they would dress it up in shirts and kiss it as though it had been God himself. And when the creature [Kempe] saw the worship and the reverence that they accorded the image, she was seized with sweet devotion and sweet meditations, so that she wept with great sobbing and loud crying. And she was so much more moved because, while she was in England, she had high meditations on the birth and the childhood of Christ and she thanked God because she saw each of these creatures have as great faith in what she saw with her bodily eye as she had before with her inward eye.

In the description, the existence of the “ass” and the act of dressing the image in shirts lead the reader to see Christ’s image in that of the baby Jesus. Finally, Kempe explicitly expresses that when she exclaims her “high meditations on the birth and the childhood of Christ.” The extreme emotions reflected here with the sobbing, and shuddered and complete sense of feeling overwhelmed with love towards a non-living baby starkly contrasts with the other extreme lack of emotions with her own children.8

Alternatively, at the beginning of the book Kempe repetitively depicts instances where she wishes

to be chaste, but must allow her husband to have his way with her, and then she would say in as much as a few words or at most a line expressing that she then had a child. For instance, after begging to be chaste, her husband responds saying, “it was good to do so, but he might not yet – he would do so when God willed. And so he used her as he had done before, he would not desist. And all the time she prayed to God that she might live chaste,” but since she could not deny her husband her body because of the marriage debt law, she expressed her grief by inflicting, “great bodily penance […] and bore him children during that time." The language here seems so detached, especially in reference to her children, to her own flesh and blood. Not only is there little information about the “children” referenced above, such as their genders, age or name, but the language itself is so detached, use of “bore” makes it seem like her wifely duty to her husband to carry children, but she doesn’t feel any internal motherly connection to them. “Bore” could also be seen as a pun, further expressing Kempe’s disinterest in child rearing, as representing motherhood as a bore.

Analyists rationalize Kempe’s behavior by “[presuming] that the physical absence of Margery's children in her account, except for isolated allusions, represents an abandonment and rejection of her own maternalism in favour of pursuing the spiritual life”. Considering this argument, Kempe’s other devout actions reiterate the presumption because throughout the novel, Kempe continually attempts to shun the Earthly material and focus on only the Holy, and that this would also include the rejection of her Earthly children. To be a mother to a limited amount of children in a limited sphere would forever prevent her from a personal experience of the body of Christ in all aspects of life, so instead Kempe finds empowerment through imitatio Mariae, merging with the persona of the Virgin whilst on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, to become mother to the whole world.10 Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

Baby Jesus Dolls

No comments:

Post a Comment